‘Burdalone’ is an old Scottish word meaning the last bird in the nest, the one left when all the other chicks have flown or all the other chicks have died. It’s a sad and lonely word, and perfectly describes Homo sapiens.

When one of the first members of our own species studied the world around her, most of what she saw would be familiar to us today, whether from personal experience or from watching nature documentaries about Africa. Extensive grasslands dotted with acacias, watering holes and narrow rivers with crumbling banks, herds of large grazing animals such as wildebeest and zebra, black herons and lizards, secretarybirds and crocodiles, a lion pride or two, and our deadliest predators – a leopard and a pack of hyenas.

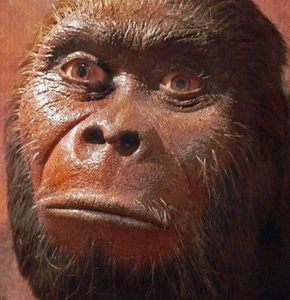

What she also saw, and which none of us will ever see, is other groups of human beings that were not H. sapiens. Like our ancestor, they were striding on two legs and using their large brains and opposable thumbs to harvest nuts and berries, sometimes to hunt or scavenge for meat, and to fend off predators. They looked very similar to us, used tools, and some may even have created art and used language to talk to one another.

Around 350,000 years ago, at this stage the earliest date we know H. sapiens might have first strode the planet[i], there was no reason to think things would ever change.

But to say that we are human today is to say that we are members of a single worldwide species. This is extraordinary because for millions of years to be human meant that you could be a member of any one of a number of different but related species.

It should not be contentious to say that all members of the genus Homo are human – after all, this is what the Latin word ‘homo’ means – but it is contentious to suggest, as I will later in these posts, that all bipedal great apes are human.

But first it’s important to state that it’s currently impossible, and may forever be impossible, to finally determine when we stopped simply being hominids – that is, all the apes except for the gibbon – and became hominins as well – that branch of the hominids exclusive to us and our human cousins; this is the point at which chimpanzees went their way and we went ours.[ii] We may never know exactly when the thousands of physical and psychological characteristics that distinguish us from other great apes evolved; what we can be sure about is that almost of them were shared with at least some of our hominin ancestors.

We are so close to our cousins, genetically and historically, that making a distinction between whether or not they are human seems farcical. Indeed, the same argument can be made for any two species close to each other in the hominin line.

In 2005, British celebrity Alan Titchmarsh allowed professional make-up artists to disguise him as a Neanderthal; he then walked along the streets of London, almost completely ignored by everyone.[iii]

At some point we need to demarcate between those species we consider human and those we consider pre-human, and to date the only specific marker that distinguishes all of us from all of them is bipedalism, not some arbitrarily determined measurement of brain capacity, morphology or dentition.

As well, research into the workings of the human brain, and into animal intelligence generally, has thrown into doubt those psychological characteristics we traditionally considered to be peculiarly human, characteristics that made us special and put us above the rest of the animal kingdom. Once upon a time, we were considered the only animal to make tools, then the only animal to make tools and smile, then the only animal to make tools, smile and do handstands.

It’s similar to a town building a bridge and claiming it’s the only bridge in the world, only to discover that a nearby town has one as well. So the first town now claims it’s the only single-span bridge in the world, until it learns there is a another single-span bridge in the next county. The first town now claims it is the only single-span bridge in the world with green arches, and so on, every new definition increasingly trivialising what makes its bridge special.

There is strong evidence that intelligence has arisen many times in the animal kingdom: in primates, cetaceans, elephants, larger carnivores such as dogs, hyenas and the big cats; birds, particularly corvids and parrots; and some molluscs such as octopuses and possibly squids.

There is also growing evidence that self-awareness and even a theory-of-mind[iv] exists in other primates such as chimpanzees and some birds such as crows.

So what are the characteristics that separate humans from our nearest living relatives, the chimpanzee and bonobo?

Before we answer that, we have to talk taxonomy and cladistics – how scientists classify living things.

Life is a spectrum

In his book The Vital Question, biochemist Nick Lane writes that ‘the distinction between a “living planet” – one that is geologically active – and a living cell is only a matter of definition … Here is a living planet giving rise to life, and the two can’t be separated without splitting a continuum.’[v]

Different scientists may employ different markers or waypoints in determining the start of life on Earth, all of which are subject to controversy and disagreement, but the truth is that there is no precise point in time when anyone could claim that a given chemical process for the first time was created by life rather than geology; it would be an arbitrary decision.

The same principle applies throughout evolution. There is no precise point in time where we can say fish gave rise to amphibians or basal reptiles to dinosaurs.

Changes in life brought about by evolution through natural selection isn’t episodic, it’s a spectrum.

But evolution does present a handful of events when with some certainty we can say a new direction had begun – a direction with significant ramifications for all life that follows.

The first of these, and covered in some detail in The Vital Question, concerns the creation of the eukaryotic cell: a morphologically complex cell that contains a separate nucleus and mitochondria, each surrounded by a double membrane. As far as we know this remarkable event occurred only once in all history[vi]. An archaeon, a single-celled prokaryote, absorbed another kind of prokaryote – a bacteria – and instead of consuming it established a symbiotic relationship.

At some point later in history, some of the descendants of that first complex cell started a symbiotic relationship with a second prokaryote invader, creating chloroplasts and starting the line that would eventually lead to plants and green algae.

More recently, the arrival of the first human was an event with tremendous ramifications for all life on earth.

But when did this happen?

The king of Spain did what?

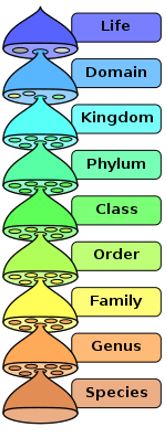

Before we go any further, we need to talk about a subject that normally works like a sedative on anyone not interested in taxonomic detail: the organisation of the taxa themselves.

I promise to keep this short and to the point, but it’s important to cover because we need to reconsider how and where our human family fits in with other living thing. And, of course, when it all happened.

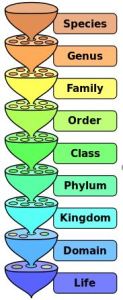

Mnemonics are as much a part of school science classes as microscopes and Bunsen burners. For example, one mnemonic frequently used in the last century for memorising the different taxonomic ranks was ‘King Philip Came Over From Great Spain’, a mnemonic for the main taxa in the Linnaean system:

- Kingdom,

- Phylum,

- Class,

- Order,

- Family,

- Genus, and

- Species.

Taxonomic ranking has been around for as long as humans have been curious about the natural world, but the above ranking developed from a system introduced by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century. He wanted to organise living things so their biological relationship to each other was made very clear. He did this by using shared characteristics to lump things together.

For example, these days all animals with fur, warm blood and that suckle their young with milk are put into one group, the class called mammals. The mammals themselves are grouped together with all animals with a backbone to form a phylum called the chordates. The chordates and animals without a backbone are thrown together into a kingdom called Animalia. More formally, taxa – the collective noun for the rankings – sharing a more recent common ancestor are more closely related than they are to taxa which share a more remote common ancestor: in other words a wombat is more closely related to a dog than it is to a crocodile, and more closely related to a crocodile than it is to a flatworm.

Linnaean taxonomy also introduced the binomial, the familiar two-name identifier used in science to classify an organism at the most detailed commonly used level, that of species. Homo sapiens, for example, is the binomial for human beings, just as Panthera leo is the binomial for lions and Quercus robur is the binomial for the English oak. The first word is the genus (plural genera), the second the species.

Taxonomy is a lovely idea, and appeals to anyone who thinks good old common sense is all you need when sorting bookshelves and tidying kitchen cupboards. For over two hundred years it was regarded as an almost fool-proof system: a place for every living thing and every living thing in its place.

But our knowledge of the natural world is not like that of our kitchen. Like the natural world itself, it is messy, chaotic, growing and constantly evolving.

In 1990, American microbiologist Carl Woese (1928-2012) suggested a new step was needed at the top of the taxonomic ladder to reflect the discovery of a whole branch of life whose existence was never suspected until the 1970s. The archaea, single-celled prokaryotes, were long thought to be a kind of bacteria, but work by Woese and other scientists revealed they are as chemically different from bacteria as we are.

The commonly accepted taxonomic ranks now start with ‘domain’, leaving us with cumbersome and self-defeating mnemonics such as ‘Determined, Kind People Can Often Follow Ghostly Screams’ or ‘Do Kings Prefer Chess On Fridays, Generally Speaking’.

Domain isn’t the only extra rank added over the decades. We also have ‘subfamily’, ‘tribe’, and sometimes ‘subtribe’, ‘subgenus’ and ‘subspecies’, and that’s just in the field of zoology.

In the story of ‘Us’ we’ll be dealing mainly with genus and species, and in the next post we’ll discuss what makes up both taxa.

Other posts in this series can be found here:

‘Us’ Part 3 – The devil in the detail

‘Us’ Part 4 – Using your noggin

[i] https://simonbrown.co/2017/10/07/07-october-2017-new-evidence-suggest-we-are-much-older-than-300000-years/

[ii] Some palaeoanthropologists include chimps and bonobos in the hominin. Rather than outlining all the arguments for or against, I’ll err on the side of caution and include only our immediate family in the hominins.

[iii] Titchmarsh did this in the wonderful natural history series The British Isles: a Natural History. See https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01fkhdx.

[iv] This is the ability to attribute mental states similar to your own to other members of at least your own species and possibly other species as well.

[v] Lane, Nick; The Vital Question; London, 2015; p 27.

[vi] This may have happened a second time. A single-celled organism with a nucleus, and possibly mitochondria, dubbed Parakaryon myojinensis, was retrieved a few years ago from the foot of a sea creature found off a coral atoll not far from Japan.

The main difference between P. myojinensis and all other eukaryotes is that its nucleus and mitochondria are surrounded by a single membrane instead of a double one, and its DNA is stored in filaments (as in bacteria) suggesting it is the result of a different line of evolution from all other eukaryotes. Indeed, there is some argument as to whether it is a true eukaryote at all. The only thing that can be said with some certainty is that it is definitely not a prokaryote.

No other example of this creature, or anything similar, has since been recovered. Nonetheless, when it comes to science, hope springs eternal …

See here for more information.